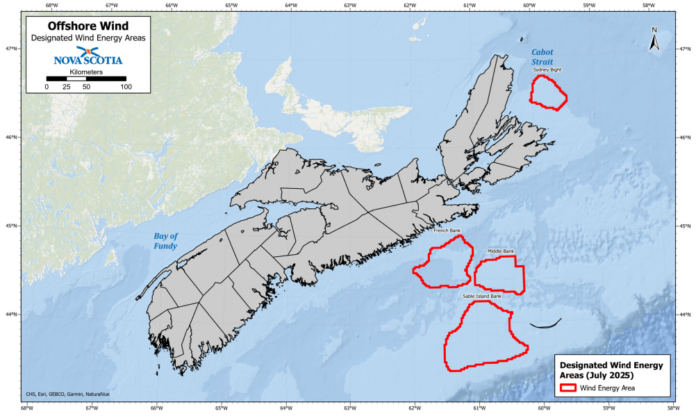

By Alec Bruce, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter Guysborough Journal CANSO: With news recently of the provincial and federal government’s designation of French Bank, Middle Bank, Sable Island Bank, and Sydney Bight as Canada’s first offshore wind areas, Nova Scotia set aloft what officials expect will become a powerful new industry – one they say will attract…